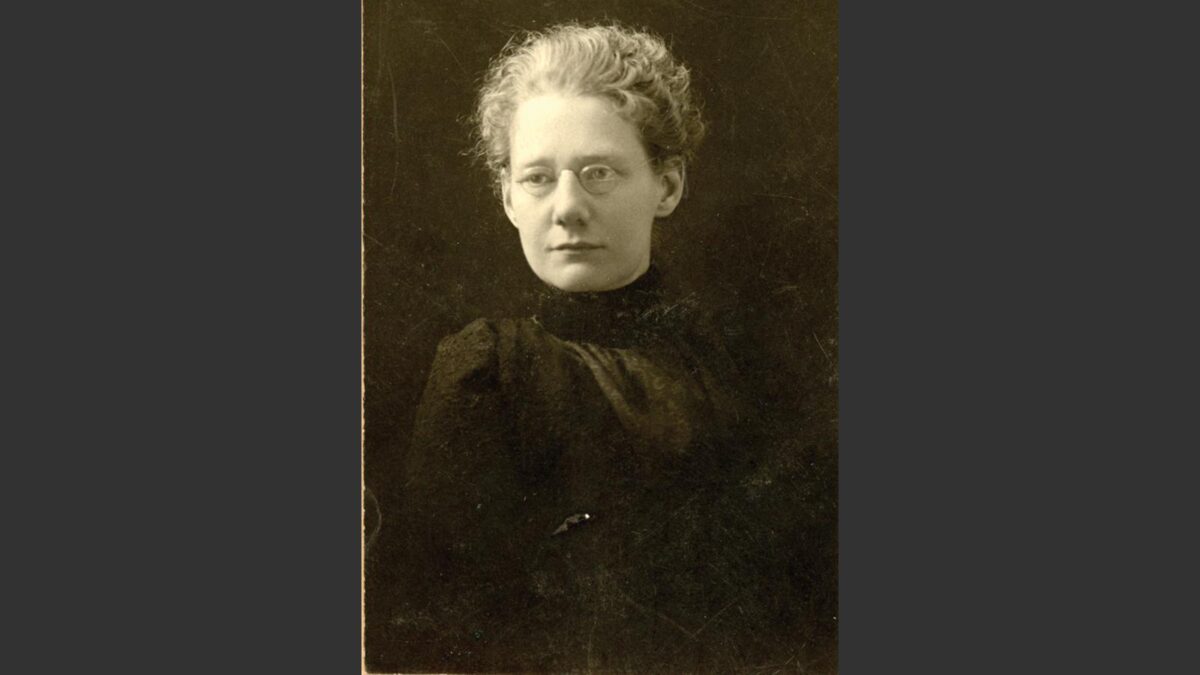

The Magnanimous Miss Dimmitt: A series celebrating the life and history of Lillian E. Dimmitt

The name Dimmitt is found on a great many things throughout the campus of Morningside University, and that name is connected to a woman who was truly extraordinary. There are many presidents, students, alumni, and donors throughout the history of Morningside who have shared many times and in many ways that without Lillian Dimmitt, there would likely be no Morningside. As time marches on, it is important to revisit those pieces of history. Over the next few editions of the Morningsider, we will share the story of Lillian Dimmitt to be reminded of the many ways she remains a living presence on the Morningside campus.

From its first day as Morningside College in 1894 and for more than seven decades, Miss Lillian E. Dimmitt served Morningside University as a beloved leader and mentor. Her 71 years of dedication to Morningside students, alumni, and colleagues made her one of the longest-serving leaders of a single institution, and her Morningside legacy continues today. As stated by Morningside President J. Richard Palmer in 1965, “Miss Dimmitt will always be more than a memory, she is a living presence in this place.”

Miss Lillian E. Dimmitt was born in Danville, Ill., on Feb. 10, 1867, to James P. and Sarah Louisa (Rush) Dimmitt. She attended schools in Danville, as well as the preparatory department of Illinois Female College (later MacMurray College) and graduated from Decatur High School. She went on to earn her A.B. degree from Illinois Wesleyan University in 1888.

Miss Lillian E. Dimmitt was born in Danville, Ill., on Feb. 10, 1867, to James P. and Sarah Louisa (Rush) Dimmitt. She attended schools in Danville, as well as the preparatory department of Illinois Female College (later MacMurray College) and graduated from Decatur High School. She went on to earn her A.B. degree from Illinois Wesleyan University in 1888.

Following completion of her degree from Illinois Wesleyan, Miss Dimmitt moved with her family to Fort Worth, Texas., where her father was serving as a Methodist minister. Miss Dimmitt’s parents boarded a retired preacher from northwest Iowa who had heard from the chancellor of the University of the Northwest back in Sioux City, Iowa, that the university needed faculty. The preacher let the chancellor know that Dr. Dimmitt had daughters who might be interested in filling the positions, so the chancellor wrote Dr. Dimmitt with the hope one of the Dimmitt daughters might be persuaded to join as faculty. There was no mention of salary or even what subject would need to be taught in the letter that was sent, but Miss Dimmitt recalls her spirit of adventure giving her the courage to tell her father she would go in reminiscences wrote that now live in the Morningside University archives.

When her father’s Fort Worth congregation learned of Miss Dimmitt’s plan, they were appalled at the notion she would consider moving to Sioux City where the University of the Northwest was located. Lillian Dimmitt shared in her reminiscences in 1957:

“Now what was the reaction of our parishioners when they found out that the preacher’s daughter was going to Sioux City immediately? Why, one of them said, “Why, Dr. Dimmitt, you surely aren’t going to let your daughter go to Sioux City! Why, yes, she is going there to teach.”

“Why, it is the worst hell-hole in the United States. Just across the river in what they call “Covington,” Nebraska, is the gathering point for criminals in America. And it isn’t safe for a woman to be on the street in Sioux City – even in the daytime.”

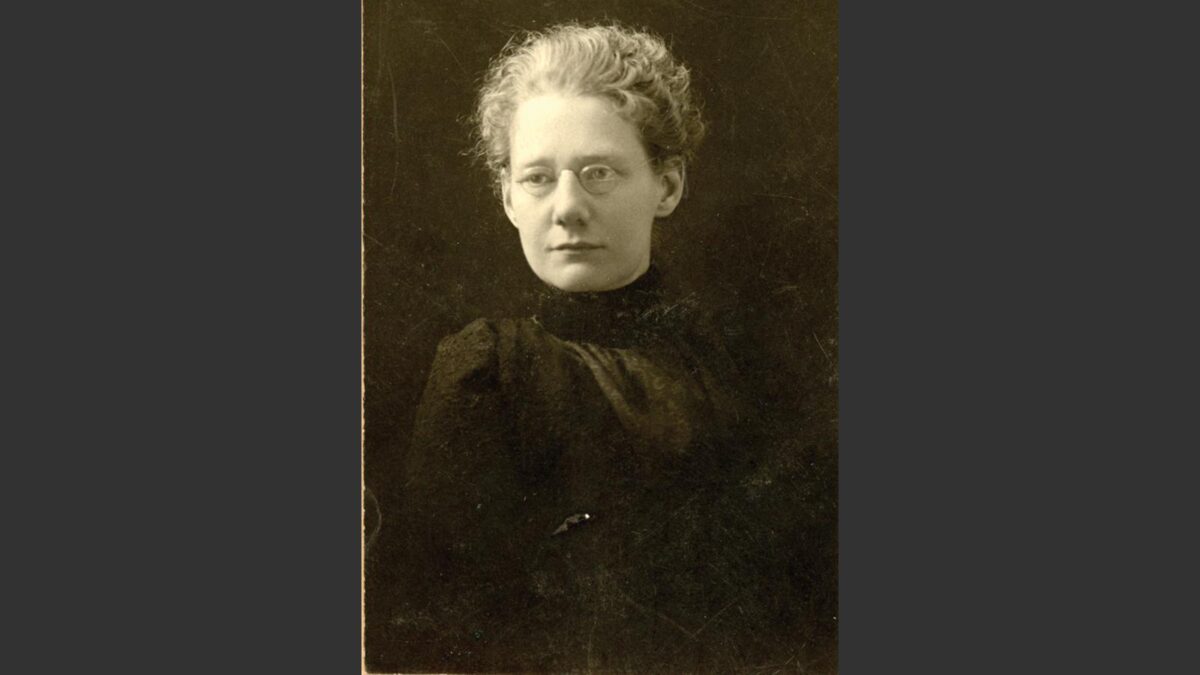

Well, they told me and that didn’t faze me…They told me that in Iowa it gets so cold that the eyes of the horses freeze in their heads. Well, I couldn’t believe that, so that didn’t faze me either. And I was ready to go.” The children of Sarah Louisa Rush and Rev. James Polk Dimmitt: Emma Franes Dimmitt Swain, Lillian English Dimmitt, George Rush Dimmitt, Della Crane Dimmitt, Lucy Paulsen Dimmitt Kolp.

The children of Sarah Louisa Rush and Rev. James Polk Dimmitt: Emma Franes Dimmitt Swain, Lillian English Dimmitt, George Rush Dimmitt, Della Crane Dimmitt, Lucy Paulsen Dimmitt Kolp.

Indeed, Miss Dimmitt did not let the warnings deter her. She arrived in Sioux City in a “blinding northwest Iowa blizzard” on Feb. 22, 1893 and was met by the chancellor of University of the Northwest, Dr. W.F. Brush. At that point, the campus was no more than a single building that was to serve all the young university’s functions. There were no steps or bathrooms; just boards yet to be assembled and the hope of becoming a respected institution of higher education.

Miss Dimmitt was a bit shocked by the state of things, but that night she was taken to a dinner where she was introduced to her colleagues and a few students.

Miss Dimmitt recounted that one of those students, Earnest Richards, provided a toast that gave her hope she had made a good choice in going to University of the Northwest, recounting, “It was poetical and rhetorical, and it was a beautiful thing – well organized. I was dumbfounded. And I said to myself, ‘Why do they have students like this at the University of the Northwest?’ So it popped through my head that I hadn’t made such an awful blunder after all in coming here.”

Unfortunately for Miss Dimmitt and the founders, the hopes and dreams upon which the University of the Northwest had been built would not be enough. The young university was struggling to find its footing as Miss Dimmitt was working to find hers. It had been conceived amidst a period of growth in 1889 by Sioux City business leaders who felt it would be an important resource for serving the booming metropolis. However, the financial depression of the early 1890s thwarted the growth of Sioux City, and the debt-ridden, young university was turned over to the law.

Miss Dimmitt shared that this was the point where she felt she had endured enough, writing, “My personal discomfort with the immediate surroundings and my disappointment over the position that was offered me meant nothing compared with the general spirit of gloom and unfulfilled dreams and uncharted futures. So, I wrote home a detailed account of my personal experiences of living quarters, no teaching contract, no salary guarantee, and no salary payments except for a few dollars. The economic situation was shallow, the unrest and uncertainty of the prospect of the institution being closed most any day. My own pride was injured with being connected with a bankrupt institution.”

Within days, Miss Dimmitt received a letter back from her father that advised her to resign. However, attached to the letter was a post-script from Miss Dimmitt’s mother. In it, her mother discouraged Miss Dimmitt from following her father’s advice. Her mother told Miss Dimmitt that returning home would weaken her resolve and potentially damage her reputation as an educator. Miss Dimmitt said her mother reminded her that life was made up of hard situations and obstacles, and that in life, it was necessary to find ways around the stone walls a person encounters to build personal strength and courage. This support from her mother not only gave Miss Dimmitt the fortitude to stay, but students would later recall that her mother’s words helped form a philosophy that Miss Dimmitt carried with her and shared throughout her teaching career, often reminding students and colleagues facing misfortune that, “The road gets better further on.”

Faculty baseball teamMiss Dimmitt stayed, and the road that she and the University of the Northwest were on found its way to the Northwest Iowa Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. These organizations filed articles of incorporation to re-establish the university as Morningside College. Miss Dimmitt recalled that the members of the board came to her and offered the opportunity to return to teach at the school following its transition to Morningside. Understandably, Miss Dimmitt had many questions about why their plan would work when the University of the Northwest had failed. She wrote: “They replied we were going through a period of transition…they said they needed someone to hold over and help keep the school running, and that I was young enough to afford to give a year of my life to missionary work. That finally persuaded me. It wasn’t exactly a Christian duty, but an open door to Christian service.

Faculty baseball teamMiss Dimmitt stayed, and the road that she and the University of the Northwest were on found its way to the Northwest Iowa Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. These organizations filed articles of incorporation to re-establish the university as Morningside College. Miss Dimmitt recalled that the members of the board came to her and offered the opportunity to return to teach at the school following its transition to Morningside. Understandably, Miss Dimmitt had many questions about why their plan would work when the University of the Northwest had failed. She wrote: “They replied we were going through a period of transition…they said they needed someone to hold over and help keep the school running, and that I was young enough to afford to give a year of my life to missionary work. That finally persuaded me. It wasn’t exactly a Christian duty, but an open door to Christian service.

So, Miss Dimmitt chose to stay on at the newly formed Morningside College, and the period that would follow would be one that Miss Dimmitt would describe as the young college’s “Heroic Age.”

Look for the story to continue in the next edition of the Morningsider.